|

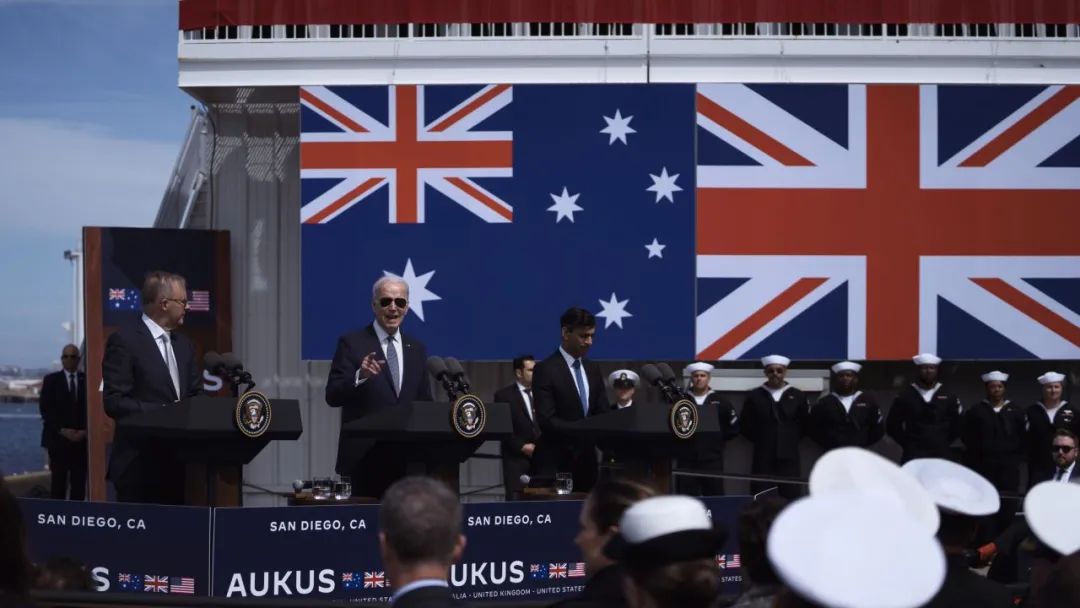

Club点评:在中美战略竞争加剧的背景下,澳大利亚面临严峻的外交平衡挑战。美国主导的"印太战略"与中国日益增强的区域经济影响力交织,使澳政府陷入“安全依赖”与“经贸利益”的两难抉择。AUKUS核潜艇项目尤其凸显这一战略矛盾,它不仅成为美国“遏制中国”战略的一部分,还可能影响澳大利亚与东南亚国家的关系。 澳大利亚资深外交官布罗诺夫斯基(Richard Broinowski )接受“Pacific Polarity”专访,分享了自己在越南任职期间推动澳越关系发展、促成澳柬关系正常化的经历,包括与洪森早年的交往故事;他认为,越南在中美之间展现出的外交平衡术值得澳大利亚借鉴:一方面坚定维护国家立场,另一方面与中国保持密切经贸合作,实现灵活务实的战略自主。 作为澳前驻越南、韩国等多国大使,布罗诺夫斯基直言,澳政府盲目追随美国推进AUKUS协议,是一项“代价高昂的战略误判”。他批评核潜艇项目不仅耗资巨大,还可能削弱澳大利亚的外交自主性,将国家安全政策“过度绑定”于美国。他呼吁堪培拉在军事战略上应当“与美国适度松绑”,以更好维护自身利益与区域稳定。 “Pacific Polarity”是一个关注亚太地缘政治的智库博客平台,由北京对话助理研究员李泽西等青年学者联合创办。 Club Comment: Amid intensifying strategic competition between China and the United States, Australia faces mounting diplomatic balancing challenges. The U.S.-led “Indo-Pacific Strategy” intersects with China’s growing regional economic influence, placing the Australian government in a dilemma between “security dependence” and “economic interests.” The AUKUS nuclear submarine project particularly highlights this strategic contradiction—it not only forms part of the U.S. strategy to contain China, but may also strain Australia’s relationships with Southeast Asian countries.In an exclusive interview with Pacific Polarity, veteran Australian diplomat Richard Broinowskishared insights from his tenure in Vietnam, where he helped advance Australia–Vietnam relations and normalize ties with Cambodia, including anecdotes from his early interactions with Hun Sen. He argued that Vietnam’s diplomatic balancing between China and the U.S. offers valuable lessons for Australia: firmly uphold national interests while maintaining close economic cooperation with China—achieving pragmatic and flexible strategic autonomy.As a former ambassador to countries including Vietnam and South Korea, Broinowski bluntly stated that Canberra’s unquestioning alignment with Washington on the AUKUS pact constitutes a “costly strategic miscalculation.” He criticized the nuclear submarine initiative as not only financially burdensome but also a threat to Australia’s diplomatic independence, effectively overcommitting its national security policy to the United States. He called on the Australian government to “moderately decouple” from the U.S. militarily in order to better protect its own interests and contribute to regional stability.  理查德·布罗诺夫斯基资料图(图源:Jom Photography摄影公司) Pacific Polarity:在本期“Pacific Polarity”节目中,我们邀请到理查德·布罗诺夫斯基(Richard Broinowski)。布罗诺夫斯基先生是澳大利亚资深外交官,曾担任澳驻越南、韩国、墨西哥和古巴的大使,并历任其他外交职务。 他曾在堪培拉大学和悉尼大学任教,担任新南威尔士州澳大利亚国际事务研究所主席,并著有八本著作。您认为这段广泛的外交生涯所获得最重要经验是什么? 理查德·布罗诺夫斯基:感谢,今天能与你们交流是我的荣幸。是的,我在澳大利亚外交部工作了36年。我认为最重要的经验是:外交——即与他人建立关系、理解他国立场、认真倾听的艺术——至关重要。外交手段远比武力手段更有效解决问题。对抗从来不是好事。我们必须让军事工业复合体退居次席,让外交成为核心。 当前亚洲的局势是,中国的经济崛起正在挑战美国。但华盛顿有些人试图遏制中国的崛起,这并非明智之举。澳大利亚夹在中间:中国是我们最大的贸易伙伴,而美国仍是传统军事后盾。因此,现在比任何时候都更需要外交而非武力。 Pacific Polarity:您提到“外交优先于武力”,这在亚洲尤为突出,许多亚洲国家强调外交的重要性。您认为与亚洲进行外交互动的关键是什么?您对澳大利亚和美国分别有何建议? 理查德·布罗诺夫斯基:首先,必须承认,特朗普目前过于关注中东,似乎无暇关注亚洲事务——除了他对中国的敌意。 对澳大利亚而言,与近邻(东南亚和北亚国家)发展建设性关系一直是重要目标。以我在越南和韩国任大使的经历为例,我们与两国建立了非常积极的关系。 以越南为例。1970年越战期间,我率议会代表团访问南越,目睹了美军对村庄和平民的破坏。我认为这是错误的,必须改变。1983年霍克(Bob Hawke)当选澳大利亚总理后,海登(Bill Hayden)任外交部长,我受工党政府邀请成为战后统一越南的首任大使。 我当时有四个任务:启动贸易和援助项目、处理战争遗留问题,包括寻找失踪澳军士兵、调查橙剂事件、以及弄清越南为何在1978年圣诞节入侵柬埔寨及撤军时间。这是艰巨的任务,也是我和我的继任者最具建设性和意义的任职——我们努力重新赢得越南的尊重与信任。如今,越南已是重要贸易伙伴,也是许多在澳难民的来源地,他们在这里开启了新生活。 澳大利亚必须深化与东盟及北亚国家的关系。尽管我们仍是美国盟友,但需保持更多独立。例如,我反对AUKUS协议——耗资3680亿澳元购买三艘弗吉尼亚级核潜艇是浪费纳税人金钱,且适得其反。我同意前总理基廷(Paul Keating)和怀特(Hugh White)等评论家的观点:我们应与美国军事行动保持距离,避免卷入其发动的战争;我们过去参与了朝鲜、越南、阿富汗、伊拉克等战争,但是以后不应再参与。当前政府和反对党均未采取正确策略。试图获取核潜艇将浪费很多钱,我认为我们最终将不得不放弃AUKUS,转而寻求更适合区域防御的武器,而非用于遏制中国。 Pacific Polarity:我想聚焦您驻越南的经历。当时东南亚国家(如泰国、马来西亚、新加坡)将一个统一的越南视为生存威胁,认为其意图吞并整个中南半岛。1983年您到河内时,越南统一不到十年,刚结束与中国的战争,又遭美国贸易禁运,与东南亚关系紧张。 在此背景下,能否谈谈您任大使期间的复杂性?越南政府如何自我改革?如何开始与外界重建关系?您在其中扮演了何种角色? 理查德·布罗诺夫斯基:这些都是关键问题。我当时的首要目标是与越南外长阮基石建立密切关系。他是位睿智的人。我曾问他职业生涯中最糟糕的经历,他回答:“在越法战争期间的战俘营里铲粪。”后来他成为外长,我们关系紧密。  1983年,越南外长阮基石访澳,会见时任总理霍克(左二)和外长海登(左一)(图源:越南外交部) 当澳大利亚外交部长海登第二次访越时,他问我阮基石能否安排他与柬埔寨领导人洪森会面。当时洪森被西方、中国、日本和东南亚等国家视为越南的傀儡;讽刺的是,国际社会那时候仍承认波尔布特为柬埔寨领袖。 阮基石安排洪森到胡志明市的安全屋会面——那里曾是英国大使官邸,我们用印有英国皇冠的道尔顿瓷器喝茶,交谈两小时。会后海登对我说:“这人不是傀儡,是真正的爱国者。”他还问洪森哪只是假眼(洪森曾为红色高棉成员,战斗中失去一眼)。我答“左眼”,他笑说:“那是真的眼珠吧。”这是笑谈,但也表明,海登看出洪森或许会“不择手段”,但应该是柬埔寨的领导人。 这次会面促使澳大利亚转向承认洪森政权,并自此与柬埔寨建立紧密关系。在澳大利亚后来的外交部长埃文斯(Gareth Evans)推动下,1992年柬埔寨首次大选,尽管红色高棉残余势力袭击选民,选举仍顺利完成。这是澳越合作的范例。 对于澳大利亚来说,越南处理对华关系的方式也值得借鉴。1979年中国“教训越南”,我不认为中国本来打算占领越南领土,只是想要教训一下越南。中方领导人最近访问了越南和柬埔寨,中越关系比过去更为建设性。与此同时,越南也保持与美国友好的关系,努力在两国中间取得平衡, 在我看来,越南是南太平洋和东南亚地区的一个支点,也是东盟其他国家学习如何同时与中国和美国发展良好关系的榜样。我在那里的时候,越南的声誉非常差,泰国甚至认为越南不会在柬埔寨边境止步,担心越南会入侵泰国。但这些担忧后来被证明是错误的。也正是在我任期期间,我开始看到越南与泰国,以及与东南亚其他国家之间的关系开始回暖。让我非常欣慰的是,如今我看到越南已经成为东盟十国中一个非常重要的领导成员。 Pacific Polarity:关于澳大利亚早期与越南的接触,有档案显示,早在上世纪60年代孟席斯政府时期,澳大利亚就曾试图利用中苏分裂,甚至“联苏抗中”,而美国当时则希望“联中抗苏”。您认为澳大利亚当初接触越南是否带有“反华”意图,毕竟当时中越关系很糟糕? 理查德·布罗诺夫斯基:孟席斯是个欧洲中心主义者,也是“白澳政策”的支持者,并将中国视为巨大威胁。还记得澳大利亚派兵支持美国介入越战的借口吗?孟席斯声称“共产主义匕首将刺穿东南亚”,越南沦陷会导致东南亚国家像多米诺骨牌一样倒下,最终威胁澳大利亚。 这当然是无稽之谈。许多右翼评论员从不承认错误;不过,也有其他人承认错误,并认识到越战是一场内战,中苏支持北越,美澳支持南越,但双方都无意殖民或控制越南。  1967年,在越南战斗的澳军(图源:澳大利亚战争纪念馆) 孟席斯之后,澳大利亚一直希望与中国发展建设性关系。我在河内时,中国大使馆规模庞大,而堪培拉对我的报告很感兴趣,尤其是关于中方外交官在说什么、想什么。我们提供了不同于西方主流观点的视角:中国并非要主宰东南亚,中越关系也非完全对立。 不过正如我所说,越南对中国的实力有清醒认识,始终寻求务实合作。反观澳大利亚,我们与中国的关系起伏不定。特恩布尔和莫里森政府多次挑衅中国(比如禁止华为)。如今我们的外交政策充满矛盾:一方面依赖美国军事保护(尽管ANZUS条约并未明确承诺),另一方面又想维持对华贸易。这是场走钢丝的游戏。 我认为黄英贤是位优秀的外长,她在党内右翼和进步派之间艰难平衡。但当前国际局势充满不确定性,尤其在东南亚。 Pacific Polarity:您提到越南处理对华关系的经验。对澳大利亚而言,最重要的邻国或许是快速崛起的印尼。两党都承认需加强与印尼关系,但除了现任政府的防务协议,进展始终有限。您认为症结何在?此外,近期传闻俄罗斯可能在印尼设军事基地,您如何看待澳大利亚的应对? 理查德·布罗诺夫斯基:之前中国派遣军舰南下时,澳大利亚媒体也有很多危言耸听的报道。 澳大利亚与印尼的关系十分重要,尽管我们并非一直认识到这一点。上世纪90年代我主管“澳大利亚广播电台”时,该电台在亚太地区的影响力已开始衰退。之前,斐济内阁会议曾暂停会议,以收听我们的新闻,印尼听众来信也曾堆积如山——但短波广播被ABC管理层视为“过时的1930年代技术”。我被迫关闭日语广播,法语广播也险些停摆,唯一亮点是开设了高棉语频道。 最糟糕的是澳大利亚对与印尼关系的漠视:ABC竟将达尔文发射台卖给基督教广播组织,任由其向印尼传播宗教内容!这绝对适得其反。我们在地区的声誉因“澳大利亚广播电台”缩减运营受损。 与印尼的关系仍然很重要。自基廷总理当年在雅加达机场的“吻地礼”以来,澳大利亚不断尝试改善关系。但同僚们仍认为我们需投入更多资源到印尼乃至整个东盟。事实上,自二战结束英国势力退出后,澳大利亚一直重视东南亚外交,向这些国家派遣优秀的外交官。认为“现在才刚开始关注”是误解。 Pacific Polarity:您2023年的著作《日本第一》结尾恰逢日本经济泡沫破裂前夕。作为驻东京外交官,您亲历了日本经济奇迹,也目睹了1980年代华盛顿因忌惮日本崛起推动“广场协议”。如今日本人均GDP比1995年低24.6%,全球GDP占比从18.21%跌至4.01%。 这种巨变对日本国际地位有何影响?我们应从中吸取什么教训? 理查德·布罗诺夫斯基:我们与日本早期关系中的紧张,实际上反映的是华盛顿内部原本就存在的矛盾。麦克阿瑟将军是战后日本占领时期的首任总督,他主导了对日本的占领,美国也起草了战后日本的宪法,其中明确规定不得维持军事力量。然而,这在美国方面后来被视为一个失误,因为美国希望快速崛起的经济强国日本能在对抗中国的过程中站在他们一边。而日本宪法中的这一限制却阻碍了美国在冷战期间将日本发展为军事强国的计划。 所谓“自卫队”实际上是一支高效的陆军、海军和空军。日本持续发展其所谓的自卫队,至今已具备了在日本周边以外地区参与军事行动的能力——如果他们愿意的话,行动范围远远超出了单纯保卫本土。  2010年,日美参与“利剑2011”军演(图源:美国海军) 我认为,日本当前面临的主要社会经济问题是人口迅速老龄化,这也是其生活水平逐渐下滑的主要原因。 我在韩国任职期间,韩国与日本一样享受到了经济增长的红利。但据我了解,如今韩国的生活水平已经超过了日本。尽管如此,日本仍然是一个极具魅力的国家。人们热情友善,是全球游客向往的旅游胜地。相比之下,欧洲一些国家已经对游客感到厌倦,尤其是意大利,而日本如今也有类似的感受,游客实在太多了。不过,它依然是一个极受欢迎的目的地。 我和妻子经常回日本,我们两人都会说日语,虽然我的已经有些生疏了,但她的仍然很好。我们的女儿是在日本出生的,儿子则拥有日本研究的博士学位。对我们来说,日本就是第二故乡,我们在那里有许多挚友。 尽管如此,我并不认为日本如今在战略意义上是一个国际强国。日本与美国一样,对中国经济实力的迅速崛起感到忧虑,对中国保持警惕。在当前保守派政府领导下,日本大概率会继续这种立场。 相比之下,韩国就是否支持美国遏制中国方面国内意见严重分裂。总统尹锡悦因六个月前在韩国实施戒严而被起诉,目前正面临极大政治压力。民众担忧韩国会回到全斗焕和李承晚时期的戒严状态,当年许多韩国民众在那样的背景下丧命。 韩日之间的历史恩怨仍未真正消除,尽管双方不断会谈、试图改善关系,但实质进展仍然有限。然而,日本、韩国以及中国,共同构成了该地区的经济引擎。对澳大利亚来说,与这三国维持贸易关系显然符合国家利益——这是一场艰难但必须完成的平衡之举。 Pacific Polarity:您曾联署公开信批评澳外交国防政策过度亲美,呼吁独立自主。在AUKUS背景下,澳大利亚应如何平衡中美关系?考虑到当下选举期间展现出的政治现实条件,如何实现你觉得理想的状态?考虑到华盛顿的不确定性,我们如何推动中国调整立场,朝着更符合澳大利亚利益的方向发展?这是否应该是个目标? 理查德·布罗诺夫斯基:我认为主要问题在于让中国承认澳大利亚的利益。中国的务实之处在于,他们清楚澳大利亚在文化、语言、历史和军事上都是美国盟友。当然,中国也明白AUKUS本质是美英澳联合遏华。其他参与遏制中国的还包括新西兰和日本;韩国暂且打个问号。 就在几年前,中澳关系还更有建设性。2020年前我任澳大利亚国际事务研究所新州主席时,中国高级代表团曾来悉尼交流,包括外交部负责南海“九段线”事务的官员。他们明确表示中国不会威胁澳大利亚或声索国。 莫里森秘密谈判AUKUS,而且瞒着工党和法国的行径充满政治算计。工党胜选后本应重新评估,但副总理兼防长马尔斯为首的一批鹰派官员却坚持推进,声称AUKUS符合澳大利亚安全需要,我认为这非常有争议。 而外长黄英贤等一些工党乃至自由党成员显然担忧这会影响对华灵活施策。 我个人认为AUKUS代表的是错误的方式。我们应该与美国的军事关系“松绑”,我认为应取消AUKUS,转而向法国、日本甚至德国采购更适合防御北部海域的常规潜艇。怀特说得好:这些核潜艇无助于保护澳大利亚,唯一用途就是帮美国在台海冲突中对抗中国。  2023年,美国、澳大利亚和英国举办首次AUKUS峰会(图源:彭博社) Pacific Polarity:您提到与美国的军事关系“松绑”;即便主张重点与亚洲发展关系的人也认为,现阶段仍然应争取让美国继续重视亚太,需维持美澳同盟以制衡中国,不宜“松绑”,因为单凭地区国家无力制衡中国。您不同意他们的看法吗? 理查德·布罗诺夫斯基:我同意前外交贸易部常秘瓦尔吉斯(Peter Varghese)所说的:美澳关系有深厚文化历史根基,这是无法忽视的。 但将我们与美国的进攻性亚太政策毫无保留地捆绑,是错误的。我们需要做的是灵活地兼顾两方面,既保持与美国的关系,又与中国发展更具建设性的关系。我认为这是可以实现的。 我不认为我们应该抛弃美国。讽刺的是,特朗普可能先抛弃我们。 特朗普不是一个多边主义者。我认为他对国际事务的认识是有限的。他的行为不可预测。如今他已经对欧洲人造成了不小的打击,欧洲方面对于他不支持乌克兰深感忧虑,并意识到将不得不重新调整自身定位,重新定义自己的防御能力,因为今后他们将无法再像过去那样依赖美国的支持。 一个关键问题是,特朗普是否会满足于仅再任一届,还是会试图连任两届甚至更多,试图把自己变成一位独裁者。希望美国能回归某种程度的理性状态,由一位更为温和、谨慎、有见识的总统再次执政;这种情况下,澳大利亚与美国的关系也许能回到以往的状态。 不过我想强调的是,通过AUKUS将我们如此明确地与美国和英国绑定,实际上限制了我们处理国际事务和东南亚关系上的行动自由与政策选择空间。 在我看来,我们面临两项挑战:一方面要维持与美国的建设性关系,另一方面则必须努力发展与中国的建设性关系。这是必须完成的任务。 Pacific Polarity:大国常低估对手:英国低估美国独立战争,法国输给普鲁士,美国在越南、阿富汗和朝鲜战争(中国参战后)也犯同样错误。如今特朗普政府认为能通过经济战和“对华脱钩”扼制中国,甚至称中越领导人会晤是“算计美国”。 这是否意味着美国再次重蹈覆辙,再次低估对手? 理查德·布罗诺夫斯基:近期所有中美兵棋推演中,美国均告失败;我认为尤其是美军低估了中国。 我女儿安娜是电影人,刚受邀赴北京使馆和深圳演讲。她回来说中国的经济活力令人震撼,尽管当前增速放缓,但仍远超美国。 我认为特朗普正在犯低估中国实力的危险错误。同样地,我认为他也低估了若轰炸伊朗将会面临的困难。我知道内塔尼亚胡一直极力主张打击他所认为的伊朗发展核武器的计划。 我在伊朗国王执政时期曾在那里工作过两年,清楚记得国王原本计划在波斯湾沿岸建造约30座核电站。而如今伊朗只有布什尔一座核电站,但它确实为伊朗电网提供了大量电力。 但要知道,伊朗可不是伊拉克那样的软柿子。这个拥有8000万人口的国家,对自身作为波斯帝国的历史充满自豪。在我看来,若特朗普屈从以色列压力轰炸伊朗核设施,将是极其鲁莽且危险的行为。 众所周知,《关于伊朗核计划的全面协议》(JCPOA)是2015年奥巴马政府历经艰难谈判达成的。而特朗普2018年撕毁协议的做法愚蠢至极,该协议至少延缓了伊朗十年以上的核武发展能力(如果伊朗真有此意图的话)。协议将高浓缩铀削减至近乎零,甚至低浓缩铀也大幅减少,叫停约9万台离心机,并允许国际原子能机构对伊朗核设施进行比其他任何国家都更严格的核查。 如今特朗普似乎重启了谈判,已举行两次会谈且即将再次会晤。虽然目前伊朗和美国谈判代表仍分处不同会议室,但总算是个开端。我衷心希望这能促成理性解决方案,既允许伊朗发展其宣称的民用核计划,又能消除特拉维夫和耶路撒冷方面的偏执压力——他们总叫嚣着若伊朗拥核就要将其炸回石器时代。我不认为伊朗真想要核武器,即便有,也只是针对以色列核武库的防御手段。 抱歉有些跑题,但回到您的核心观点:特朗普确实低估了许多国家。如您所言,他在越南问题上就犯了错,没意识到那是场存在顽强抵抗的内战。如今对中国同样如此,这种低估极其危险。我们应该置身事外,既保持与美国的友谊,又不卷入必败的对华战争。 Pacific Polarity:感谢您的分享。 理查德·布罗诺夫斯基:谢谢你们。 英文原文如下: As the US-China trade war escalates, US President Donald Trump has temporarily exempted imports from other countries from the punitive tariffs he announced on April 2. He is reportedly trying to bully others into limiting their economic ties with China in exchange for a deal. Washington aims to isolate China, but the opposite is happening. Jersey Lee In this episode of Pacific Polarity, we're speaking with Richard Broinowski. Richard Broinowski was a career diplomat in the Australian foreign affairs and trade, having served as ambassador to Vietnam, Korea, Mexico, the Central American republics and Cuba, as well as other earlier diplomatic posts. He taught at the University of Canberra and the University of Sydney, was president of the Australian Institute of International Affairs of New South Wales and is the author of [eight] books. So given your broad diplomatic appointments across the world, what would you say are the biggest lessons that you have learned throughout that time? Richard Broinowski Well, thank you, Jersey, and it's a pleasure to be with you today and Richard. Yes, I've spent 36 years in the Foreign Service of Australia. I guess the most important lesson I've learned is that diplomacy, the art of getting on with other people, of understanding another national point of view, of listening carefully to people, is very important and that diplomacy, diplomatic solutions are much more important than solutions that lead to war. Confrontation is never a good thing. I think that we must get back to a situation where the military industrial complex is less important and that diplomacy is much more important. We have a situation in Asia now where we have the economic rise of China, which is challenging the United States. But there are people in Washington who want to contest China's rise, and that's not a good thing. And Australia is caught in the middle of this because China is our greatest trading partner, and the United States is still our traditional military back-up if we get threatened. So, yes, it's more than ever a time of the need for diplomacy over force. Jersey Lee As you say, it's the time for diplomacy instead of force. And this is particularly true of Asia; you know, lots of Asian countries like to talk about the importance of diplomacy. What would you say is key to diplomatic engagement with Asia? Both in terms of Australia, and obviously Richard comes from America, do you have any advice for the Americans in terms of diplomatic engagement with Asia? Richard Broinowski I think that for a start, we must acknowledge that Donald Trump is focused so much on the Middle East at present that he doesn't seem to have very much time to monitor developments in Asia, except in connection with his antagonism towards China. For Australia, it's always been an important objective to develop constructive relations with our near neighbours, with the countries of Southeast Asia, and with the countries of North Asia. In my experience as ambassador to Vietnam and to Korea, we developed very constructive relations with both countries. Take Vietnam, for example. I went there in 1970 during the Vietnam war, leading a parliamentary delegation to South Vietnam. And I saw the destruction that was going on by American forces against villages and the civilian population of South Vietnam. And I felt that this was wrong and that something would have to be done about it. When Bob Hawke was elected Prime Minister of Australia in 1983, Bill Hayden was his foreign minister and I was invited by the Labor government, to be their first ambassador to a post-war united Vietnam. I had four tasks. I had to start a trade program, start an aid program, finish all the unfinished business of the war, including trying to find missing in action Australian soldiers and having a royal commission into Agent Orange, and also find out why the Vietnamese had invaded Cambodia in Christmas Day [1978], and when, or if, they were going to leave. It was a big task and it was my most constructive and interesting posting, also for my successors, as part of our efforts to win back the respect and the trust of the Vietnamese. Vietnam is now one of our more important trading partners and also the origin of many Vietnamese refugees who've come to Australia and created constructive lives here. I think that Australia more than ever needs to develop and expand our relations with the countries of ASEAN and the countries of North Asia. I think that we have to keep in mind that while we remain an ally of the United States, we also have to create more distance and develop more independence. And I must say I'm against the AUKUS arrangement where we are committed with enormous amounts of money, $368 billion, to purchasing three Virginia-class nuclear-powered submarines. I think that is counterproductive and a waste of taxpayers’ money. I agree with Paul Keating and Hugh White and other members of the progressive commentariat in Canberra that we should distance ourselves militarily so as not to have to participate in any war that the United States chooses. We've been drawn into US wars in the past, in Korea and Vietnam, Afghanistan and Iraq, but we shouldn't have to do it again. So, yes, there's a challenge here, and I don't think the Australian government or the Australian opposition really have the right approach to this. I think that acquiring nuclear-powered submarines will be a very expensive exercise, and I think that we will in the end have to resile from the AUKUS deal and get back to acquiring weapons more appropriate to our regional defence and not designed to contain China. Richard Gray I want to take a moment to focus on your time in Vietnam. As a point of context, a lot of my research had focused on the Cold War in Asia and the geopolitics surrounding Singapore's foreign policy. One of my sort of big takeaways from doing that archival research in Singapore was that a lot of the Southeast Asian governments, Thailand, Malaysia and Singapore in particular, viewed a unified Vietnam as an existential threat and genuinely viewed the threat of Vietnam's intention to annex all of continental Southeast Asia as credible. When you arrived in Hanoi in 1983, Vietnam had been unified for a little less than a decade. They fought a war with China less than four years prior, and this unified country was now reeling from a trade embargo by the United States and distant relations with the rest of Southeast Asia. With that framing, could you describe some of the other intricacies of your time as ambassador? How did the Vietnamese government try to reform itself in the period you were there? And how did it start to build the process towards expanding relations with the outside world? And as you were trying to grapple with these massive changes within Vietnam and in the region, what role did you play in trying to facilitate some of these engagements? Richard Broinowski Those are crucial questions, Richard. I must say my first aim was to develop close relations with the Vietnamese foreign minister, Nguyễn Cơ Thạch. He was an intelligent man. I asked him what had been the worst experience in his professional life? He said, shoveling shit in a prison of war camp during Vietnam’s war with the French. He later became foreign minister, a highly intelligent man. With him, I developed a close relationship, so that when my foreign minister, Bill Hayden, paid his second visit to Vietnam under the new regime, Bill asked me whether it was possible for Nguyễn Cơ Thạch to help him get introduced to Hun Sen, one of the two leaders of Cambodia. At the time, Hun Sen was regarded as a satrap of Vietnam by many Western and South East Asian countries including the countries you mentioned, Thailand and Malaysia and Singapore. And certainly by China, by the United States and Japan. And the ridiculous situation at the time was that we all were still recognising Pol Pot as the leader of Cambodia. So Nguyễn Cơ Thạch arranged for Hun Sen to come to Saigon, to Ho Chi Minh City, where Bill and I met him with me at a safe house. And the safe house was quite surrealistic. It was the former British ambassador's residence in Saigon. We had tea out of dalton china with the British crown on it as we talked across the table for two hours to Hun Sen. At the end of it, Bill said to me, that man is no satrap. He is a genuine patriot of Cambodia. He asked which is his glass eye? (Hun Sen had been a member of the Khmer Rouge at one stage and he lost an eye in a conflict). And I said, it's the left one. He said, yeah, that's the human one. It was a joke, but it was indicative of the way Bill summed up this man as possibly ruthless, but also a genuine leader of Cambodia. As a result of that meeting Australia changed its recognition from Pol Pot to Hun Sen. And since then, we have developed close relations with Cambodia as well as Vietnam. Gareth Evans was very much involved in the first independent general elections held in Cambodia in 1992, which worked well, and a lot of Cambodians came, even though they were still being attacked by the remnants of the Khmer Rouge. They came to the elections and voted. But unfortunately, Hun Sen has since then become a dictator and no longer is there democracy in that country. But it was one example where Australia played a constructive cooperative relationship with Vietnam. I think that also Australia can learn, if I can move forward from that, to looking at the way Vietnam has handled its relations with China. The Chinese attacked Vietnam in 1979 to ‘teach them a lesson’ for invading Cambodia. But in fact, the Chinese were the ones who were taught a lesson. The Vietnamese were battle-ready, and they resisted the Chinese incursion and sent them packing. I don't think the Chinese meant to occupy Vietnam for any length of time. It was a salutary gesture to tell the Vietnamese that they were not happy with them. However, since then, every time they've had to, the Vietnamese have stood up to the Chinese - particularly over disputed claims to islands in the South China Sea. But they've cooperated with them as well; the Chinese leader has been to Vietnam recently and Cambodia, and the relationship is very much more constructive than it was before. But apart from that, the Vietnamese also keep relations open with the United States. And so they're playing a balancing act. They're a fulcrum, in my view, in the South Pacific, in the Southeast Asia sphere, an example for other countries in ASEAN to develop good relations both with China and the United States. When I was there, Vietnam's name was mud. Especially among Thai officials, who thought that the Vietnamese were not going to stop at the border of Cambodia, that they were going to invade Thailand as well. That proved to be false. And I began to see a thawing of relations between Vietnam and Thailand as well as the other countries of Southeast Asia when I was there. And to my great pleasure, I now see Vietnam as a leading member of the ten countries of ASEAN. Jersey Lee A quick follow-up on that. Would you say that Australia's early efforts to engage with Vietnam were intended as an anti-China move, given tense relations between China and Vietnam at the time? Because actually, recent archival research here in Australia have shown that even back in the days of former Prime Minister Menzies in the 1960s, there were already efforts in Australia to take advantage of the Sino-Soviet split, specifically in that Australia should try to team up with the Soviets, whereas the Americans at the time were thinking of teaming up with the Chinese. Could you briefly comment on that? Richard Broinowski Yeah, Menzies was a Europeanist. He was a champion of white Australia. He had conservative ideas. To Menzies, China was the big menace. You remember the myth that was developed at the time for why Australia should send troops to support the United States in South Vietnam? It was because Menzies thought that China was going to drive a Communist dagger down through the whole of Southeast Asia; that Vietnam was an example of a country that was going to fall, and that would lead to, the rest of the ASEAN countries falling like dominoes as well, leading eventually to a threat to Australia. This was all, of course, nonsense, as it proved to be later on. I must say that many right-wing commentators on the international stage often don't admit their errors. On the other hand, some commentators do admit their errors and, on reflection see that Vietnam was a civil war, in which both China and the Soviets backed the North, and the US and its allies, the South, but not to the extent of seeking control or colonisation Concerning our own relations with China, since Menzies, we’ve consistently wanted to develop constructive relations with China, and how they perceive their own relations with their Asian neighbours. In Hanoi, China maintained a large Embassy, and Canberra was very interested in my reporting, on what Chinese diplomats were thinking and saying. We were giving Canberra a counterpoint view to the prevailing Western one that China was out to dominate Southeast Asia, and that China-Vietnam relations were at loggerheads. But as I said, the Vietnamese were and are realistic about China, about its huge power, and they want to have as constructive relations with Beijing as they can. As for Australia, we've had ups and downs in our relations with China. I think the Morrison and Turnbull governments did a lot to antagonise China - Turnbull especially in prohibiting Huawei from operating here. And now we have this almost contradictory foreign policy in Canberra. On the one hand, we put great faith in our great and powerful friend, the United States, to protect us militarily, even though ANZUS promises nothing of the sort. On the other, we want to develop and maintain constructive trade relations with China. It's a balancing act. Penny Wong, in my view, is a good foreign minister. She's doing the best she can, and she's being split between the right wing of the Labor Party and the opposition on the one hand, and more progressive elements within the government on the other. But let's wait and see. As everyone says, it's a time of great political turmoil and uncertainty in the international situation, particularly in Southeast Asia. Jersey Lee So closer to home, you previously mentioned how Vietnam handles its relations with China as a neighbor. For Australia, probably the most significant neighbor, to some extent of the word, would be Indonesia, which is rapidly growing. And everyone in Australia, both parties agree on the need to engage with Indonesia and agree that we need to do more. However, beyond a defense pact from this current government, the relationship has never really seemed to progress sufficiently, or to anyone's satisfaction, hence why everyone keeps on talking about the need to do more. So in your view, why has that been the case and what can be done to change the trajectory? And also, if you could briefly discuss the recent reports suggesting there might be a potential Russian base in Indonesia, how do you think that situation has been handled by Australia given the current election? Richard Broinowski When the Chinese recently sent a flotilla of ships around Australia, there was a great deal of alarmist reporting in the press about that. Australia’s relations with Indonesia are extremely important, but we have not always seen them as such. When I was general manager of Radio Australia at the beginning of the 1990s, the strong influence we had with our broadcasting into the South Pacific and Southeast Asia was beginning to erode. No longer would a cabinet meeting in, say, Fiji, be paused while ministers listened to RA news. No longer were our mailbags from Indonesia as heavy as they had once been. Shortwave broadcasting was seen by ABC management as a 1930s technology. I was compelled to close down our Japanese language service and it was touch and go whether we could maintain our French language service. The only positive development during my watch was starting a Khmer language service. And worst of all was our disregard for relations with Indonesia, when it was decided by ABC management to sell our Darwin transmitters to an international Christian group of broadcasters who used the transmitters to broadcast Christian messages into Indonesia. This is counterproductive to say the least. I think we've lost a great deal of kudos, our image in the region has been reduced by the depletion of Radio Australia resources. But of course, Indonesia is extremely important. Since the time that Paul Keating went there as Prime Minister and kissed the ground when he got off the plane in Jakarta, I think that some things have been done to expand and improve the relationship. Nevertheless,I keep hearing from colleagues that we have to spend more time and more effort, not just in Indonesia, but the rest of the ASEAN countries, to develop Australia's diplomatic presence further. But in my view, we always have done that, ever since the end of the Second World War, when Australia began its own international diplomacy. Before that, we relied on the British, of course. But ever since then, we have made a practice of putting good representatives into the countries of Southeast AsiaSo I think it's a mistake to think that we're only just beginning now to focus on the countries of Southeast Asia. We've done that ever since the post-war period. Richard Gray In preparation for this interview, one of the things that I read was your 2023 book chapter, Japan is Number One. And one of the things that struck me was where it ends, which is just before the start of Japan's economic crisis and the end of the 1990s. So from your earlier post as a diplomat in Tokyo, you witnessed firsthand the Japanese economic miracle. Then decades later in the 1980s, Washington began panicking with the thought that Japan was a competing superpower and this sort of mindset eventually led to the Plaza Accords. Viewing the crisis of Japan's economy, there were two statistics that really stand out to me. So the first is Japan's GDP per capita today is 24.6% lower than it was in 1995. And the second is that Japan's share of global GDP peaked in 1992 at 18.21%. Today it has shrunk to 4.01%. And so these are pretty seismic shifts in the global and Asian economies, but also in global power. Could you describe what it has been like to witness Japan's post-World War II ascension, contrasted by the lost decade and the continued stagnation in the present, What lessons are there in this chain of events and how has that stagnation impacted Japan's role in the world? Richard Broinowski Richard, the earlier tension in our relationship with Japan reflects a tension that existed in Washington. General Douglas MacArthur was the first governor in occupied post-war Japan. He led the occupation and the United States drafted the Japanese post-war constitution in which having the maintenance of armed forces was illegal.. But that, of course, turned out to be a tactical mistake on the part of Washington because they wanted Japan, a rising, fast-rising economic power, on their side against China. And, of course, the constitution stultified any plans the United States had during the resulting Cold War to turn Japan into a military powerhouse. The so-called self-defense forces are in fact a highly efficient army and a navy and an air force. The Japanese have continued to develop their so-called self-defense forces to the point where they now have the capacity to take part in military operations outside Japan’s immediate area of concern if they wish to, much further afield than just defending Japan itself. I think the main socio-economic problem Japan now has is a rapidly aging population. That's the main reason why its standard of living has been gradually falling. When I was in Korea, the Koreans were enjoying the same economic advantages and development as Japan. But now Korea's standard of living, from what I've read, is higher than that of Japan. Japan is still a wonderful country. People are so helpful and friendly, and it's a mecca for tourism. And where the Europeans are becoming rapidly tired of tourists especially the Italians; in Japan, they're feeling the same thing because there are too many tourists coming. But it's still a very popular destination, as you know. My wife and I go back to Japan quite frequently. We both speak Japanese. Mine is a bit rusty now. Hers is better. Our daughter was born there. Our son has a PhD in Japanese studies. So Japan is our second home. And we have so many good friends there. But I don't see Japan even now as an international powerhouse in any strategic sense. The Japanese share the United States anxiety about China’s rapid rise in economic power and being wary of China. Under a current conservative government, the Japanese will continue to do that. The Koreans, on the other hand, are very much divided about whether to support American efforts to contain China. [Yoon Suk Yeol], the president who has been indicted for introducing martial law six months ago in Korea, is now in deep hot water because of the people's fear that Korea itself might revert to a situation under Chun Doo-hwan and Syngman Rhee, where they had martial law and many, South Koreans were killed. The Koreans and the Japanese still have a history of animosity. It hasn't really come to anything much, even though they have talks all the time and try and improve relations. But, you know, Japan and Korea are, along with China, the economic powerhouse of the region. And it's in Australia's best interests to maintain the trade relations with them all. It's a challenging balancing act. Jersey Lee So you mentioned balancing act, particularly in the sense of China at the very end. You had signed onto an open letter saying that Australian foreign and defense policy has become too aligned with the United States, and call for more independence of action. How should Australia balance between the US and China, especially in light of AUKUS? Given current political realities here that you can obviously see, given the rhetoric in the ongoing election, what do you think would be a realistic pathway to move towards your ideal approach? And also given the current uncertainty coming from Washington, how can Australia seek to balance against China or to kind of push China in a direction that might be more aligned with Australia's interests? Should that even be a goal in your view? Richard Broinowski I don't think it's in our interest to present China with policies that would necessarily align with their own interests. The challenge is to get China to recognize Australia's interests. And I think the Chinese are realistic about this. The Chinese realize that Australia is culturally, linguistically, historically, militarily an ally of the United States. They know this. They also know that AUKUS is basically designed to contain China by the United States with its allies, particularly the Australia, New Zealand and Japan. Over Korea, there is a question mark. I look back only a few years ago to remember much more productive bilateral relations with China than at present. When I was president of the Australian Institute of International Affairs in New South Wales before 2020 for example, several senior Chinese delegations came and talked to us in Sydney at Glover Cottages. They included an official delegation led by the head of the Chinese Foreign Ministry's department responsible for maintaining the dashpoint lines delineating what they regarded as Chinese territory in the South China Sea. And they came to Australia to talk to us and to assure us, that China did not threaten us or other littoral countries with conflicting claims to the maritime area. Prime Minister Morrison's decision in 2022 to negotiate AUKUS without engaging the Labor opposition until the very last minute, or keeping the French informed, was an exercise in cynical politics. On winning the 2023 election, Labor should have called for a thorough investigation before agreeing to its terms. Now, our Deputy Prime Minister and Defence Minister Richard Marles leads a coterie of, I think, militaristic public servants and others, who double down on supporting AUKUS as being in Australia’s best defence interests, a position which is highly debatable. On the other hand, Foreign Minister Penny Wong and other members of the Labor government and even some Liberals who probably are deeply concerned that such a defence commitment ties Australia’s hands against cultivating a flexible approach towards China. And I think personally, it's absolutely the wrong approach. We should loosen our military ties with the United States. I think, in fact, we should cancel the AUKUS deal and go back and talk more to the French possibly the Japanese, possibly the Swedes, possibly the Germans, about getting modern, conventionally powered diesel-electric submarines that are better designed to defend our northern littoral boundaries. And Hugh White is quite right, I think, when he says these nuclear juggernauts, these submarines that we're getting from the United States, are inappropriate for the defence of Australia. They're there for one reason, and that is to help the United States contain China. Jersey Lee You mentioned loosening ties with the U.S., but even many people who argue in favor of more independence of action, more engagement with Asia, etc., say that at this stage, even as we see greater engagement with Asia, we shouldn't really loosen our ties with the U.S. We should still want to keep the alliance moving forward, we should want to keep the US engaged in the Indo-Pacific, because right now we still do need their power in order to balance China, and it's not something that Australia and regional powers alone can do. Would you disagree with their view on that? Richard Broinowski Peter Varghese, former Secretary of Foreign Affairs, now Chancellor at the University of Queensland, has made the point that our relations with the United States, have deep roots, cultural roots, linguistic roots, historical roots. That can't be overlooked or ignored. But tying ourselves ineluctably to American defence policy, which you could characterise as an aggressive policy in the Pacific, is a mistake. What we need to do is have the flexibility to do both things, maintain our relationship with the United States while developing more constructive relationships with China. And I think that could be done. I don't believe that we should abandon the United States. The irony is that under Donald Trump, the United States will more likely abandon us. Trumpis not a multilateralist. He is a man of, I think, limited knowledge about international affairs. He's unpredictable in what he's going to do. He's already taken a drubbing to the Europeans and they're very worried about his lack of support for Ukraine, and the fact that they're going to have to realign themselves and redefine their own defense capabilities, because they're not going to have the United States to support them much more. The big question there is whether Trump will tolerate only having one more term, or try and have two or even more terms, turn himself into some sort of dictator; The United States will hopefully get back to some degree of sanity, where a more moderate, careful, knowledgeable president might preside again, in which case, Australia's relations with the United States might return to what they were before. My point, though, is that by aligning ourselves through AUKUS with the United States and Britain so definitely, limits our options for freedom of solutions, or freedom of action, how we're going to handle our international affairs and our Southeast Asian relations. In my view, we have two challenges. One while maintaining constructive relations with the United States, is to cultivate more constructive relations with China. That has to be done. Richard Gray As an extension from this, as we think about US policy, and broader international relations structures, it seems like for great powers, there's a problem where great powers underestimate their adversaries. As the case in the 1770s, where the British underestimated the sort of nascent yanks, this is true in the 1870s, when the French underestimated the Germans. Again, in my country, the United States has a long record of this. We underestimated, as you know, quite intimately the Vietnamese, but also the Afghans. And in the case of the Korean War, the Chinese incursion after the coalition marched beyond the 38th parallel. Now, the Trump administration seems to hold the view that they can unilaterally conduct a sort of economic blitzkrieg on the Chinese economy with the dual pronged approach of trying to destroy China's economic development and also force the rest of the world to decouple from China. And to this end, after the Chinese leader recently visited Hanoi, Trump described that meeting as trying to screw the United States. I think one of the key takeaways for Southeast Asian states is that they have to choose between economic relations with the US and China, and engagement with China means no engagement with the United States. I guess my question with these dynamics in place, is the United States once again underestimating an adversary and once again, therefore, underestimating China? Richard Broinowski In all the war games held recently, war games involving China and the United States, the United States has lost. And I do agree with you that the US military particularly is underestimating the enormous power of China. My daughter, Anna, a filmmaker, has just been invited to give talks in Beijing at the Australian embassy and in Shenzhen in the South. She came back and said the economic growth of the Chinese is just amazing, the way they're going. And although China's economic indicators are not as bright right now as they have been in the recent past, China's development is still streets ahead of that of the United States. I think Trump is in danger of underestimating China's power. In a similar way, I think Trump is also underestimating the difficulty he would have if he started bombing Iran. I know that Netanyahu's been very keen on having a strike against what he regards as Iran's developing nuclear weapons industry. I served two years in Iran when the Shah was in power, and I knew that the Shah wanted to have about 30 nuclear power reactors along the Persian Gulf. There’s only one at Bushehr at present, and that does provide much power for Iran’s electricity grid. But, you know, Iran is not a push-over like Iraq. Iran is a country of over 80 million people with enormous pride in its own history as Persia. And it seems to me that it would be an extremely reckless and dangerous thing for Trump to give in to Israeli pressure to bomb Iran's nuclear facilities. The Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA) was, as you know, negotiated with great challenge in 2015 during President Obama's watch. And Trump walked away from that in 2018, which was such a stupid thing to do, because the Plan delayed for at least 10 years or longer Iran's capacity, if it had the motive to do so, to develop nuclear weapons. It cut back to almost zero highly enriched uranium. It cut back even low enriched uranium. It stopped about 90,000 centrifuges and it allowed the International Atomic Energy Agency to send teams in to inspect Iran's nuclear facilities in a more thorough way than any other country has been subject to by the IAEA. Now, Trump seems to be restarting talks and there have been two meetings with another coming up. The Iranians and their American negotiators are at present in separate rooms, but it’s a start.I've just got my fingers crossed that that might lead to a sensible solution, in which Iran is allowed to develop what it claims to be a civil nuclear program, without the paranoia of, the pressure of Tel Aviv and Jerusalem insisting that they're going to bomb the hell out of Israel if they get the bomb. I don't think Iran wishes to get its own bomb, but even if they do, it would be a defensive mechanism against Israel's own nuclear weaponry. Sorry, I'm diverting off a bit here, but I do think that to get back to your main point, Trump does underestimate many countries. He did in Vietnam, as you say. He wasn't aware that it was a civil war and there was such a strong resistance. And now to China, and it's the most dangerous thing to do. And we should be able to stand aside from that, still be America's friend, but not get involved in a war with China, which I think we'd lose. Richard Gray I think that concludes most of our general questions here today. Thank you so much. It's been lovely speaking with you today. Richard Broinowski Richard, thank you very much. Jersey, thank you. 原链接: https://pacificpolarity.substack.com/p/in-conversation-with-richard-broinowskis “中国主导的秩序”会是什么样?——周波谈《世界应该惧怕中国吗?》与地区安全的未来 在“选边”与“自主”之间,亚洲时代已来|多极视角 “自由主义国际秩序”?这不过是一种历史近视 (中英对照) 网络是“温水”,网民不能当“青蛙”——从澳大利亚提升恐怖威胁级别说开去 |